Articles

Articles

- Blaming the Feminists: Attempts to Debilitate a Movement

- Poetry’s Power to Speak the Unspeakable: the Kurdish Story

- Crossing Material and Metaphorical Borders

- Patriarchy and Familicide in the Case of Amanj and Lana

- Poetry Manifesto: “We will not be Bystanders”

- Sherko Bekas’ Butterfly Valley: Translator’s Preface

- Towards Becoming a Aurvivor, Êzidî Women Shedding their Shoes

- The Pleasure and Duty of Writing

- Switching Languages: a Hindrance or an Opportunity?

Blaming the Feminists: Attempts to Debilitate a Movement

London School of Economics, Gender Justice and Security Hub Blog, 2020

As a feminist who engages in knowledge production, education, and activism, I am well aware of how feminists are

silenced, our concerns are undermined, and our integrity is attacked. The continuous condemnations, intended to defame,

exhaust, and silence us, happen when we are still alive. But we also know that, like so many before us, our critics may

misinterpret our actions or write us out of history after we die. This is an attempt to correct some of the distortions

about the women’s movement in Kurdistan-Iraq, pre-empt future ones, and set the record straight.

Directed by sexist and politically motivated media (including social media), patriarchal and conservative religious

norms, or disconnected conceptions of feminism, the backlash and defamation campaigns against feminist activists are

particularly visible whenever there is an incident of gender injustice: a man murders a woman, a man rapes a child,

politically connected men compromise a trial, a media channel sponsored and headed by men degrades women. At such

moments, instead of directing their anger at perpetrators and those in power, many people blame activists. We are

accused of being “corrupt,” “careerist,” “disconnected from poor women”, “intellectually empty,” and even of being a

“mafia”.

Obviously, social change is a slow process and the path is fraught with backlash. If we do not always succeed, it is not

because we misunderstand feminism, nor is it because we are not resourceful or smart enough to fight the fight. It is

because of the resilient patriarchal system that fights us back in visible and invisible ways. This system changes laws

but does not implement them, mandates gender studies but does not provide the resources or training to succeed, creates

Gender Units in ministries but adds this responsibility on top of whatever else that staff are doing, utilises a quota

system but chooses women based on political loyalties rather than capability, and engages in defamation campaigns and

cyberbullying to undermine women activists and destroy the community’s trust in them.

Poetry’s Power to Speak the Unspeakable: the Kurdish Story

London School of Economics, Gender Justice and Security Hub Blog, 2020

As a poet, I believe it is my duty to ruin the façade of normality and fairness that prevails. The status quo is full of

injustice and inequality, full of voices that are shut out because we want to move on from the past and we no longer

want to hear its stories. It is full of injustice towards women who are regularly killed, silenced, and disrespected. We

need to problematise normality and bring to the centre what is usually relegated to the margin.

At times, I am disheartened to see members of my community turning the most awful things into jokes, failing to act

appropriately at desperate times, no longer capable of feeling shock, sadness, or outrage when injustices take place.

Feeling numb may be necessary when you need to survive successive traumas, but when it becomes a long-term trait, it is

tragic. My poem, Homeland, what shall I do with you? (Considering the Women, 2015) addresses this public numbness when

male bystanders record the recovery of two sisters’ bodies from a pond as the police drag them out with rope, destroying

evidence. In the poem I wonder if this apathy might be: “the heritage of violence,/ which has turned us into a people/

who know no mercy, feel no guilt,/ and are never shocked?” In a more recent unpublished poem, Watching Rojava, I embrace

my pain and outrage because I know “for as long as you feel/ this pain, you’re human, you’re alive/ you will resist.”

Crossing Material and Metaphorical Borders

Introduction to Martyn Crucefix’s Cargo of Limb, 2019

My first conscious experience of crossing a border was that of the Iraq-Iran border, when an Iraqi amnesty made it possible for us to move back home. I was a young child. I expected an exciting crossing to a different place which, I was told, was my homeland. I expected the border to be concrete, substantial, even grand, the kind that would signal being on a threshold- the end of an era and the beginning of a new one, the end of one country and the beginning of a new one. To my surprise, one iron chain separated Iran from Iraq. The border crossing was inconsequential and even dull. The excitement was also killed by the fact that the new land was not at all different from the one I was leaving behind. I had been cheated, lied to, made to think that homeland was a fairy tale world where I would be safer, happier.

But that was only my first homecoming and one that I had not chosen. 26 years after leaving Iraq for the second time, I returned home for good in 2014. For years, while settled in London, I kept going home to visit family, conduct research, get over my homesickness. I would fly to Istanbul and then to Diyarbakir. From there I had a 6 hour ride to the border (littered with hostile check points), and then another five hour ride to my city. Finally, the longing is over and I am home. I often think about how lucky I am to be able to return home when many forcibly displaced people are held back by war, violence, and borders.

Patriarchy and Familicide in the Case of Amanj and Lana

AUIS Voice, 2019

“He killed her, he killed her, he killed her!” It might take an era for this sentence to stop ringing in my ear. For me,

these three words express a bitter truth that many do not want to believe. The truth that in the patriarchal system and

in the name of love, a man who seems gentle and humane can murder his wife and child because she no longer wants to live

with him.

I am continuously amazed by our society’s views and definitions of “good” and “bad” men. I am shocked when I see that a

man’s mistreatment of a woman, his oppression of her, his violence, his control of her body and life, do not become

reasons to see him as disagreeable. This is because most people believe these things are “personal and private” issues

and therefore do not concern them.

The main reason why patriarchy continues is the silence and neutrality of most men, including writers, artists,

politicians, businesspersons, administrators, and even those who consider themselves to be advocates of truth and

justice. In her noteworthy book about Masculinity, Raewyn Connell talks about this phenomenon, referring to such men as

“complicit”. Men who are complicit in patriarchy do not necessarily beat women themselves, but they are bystanders and

they do not confront perpetrators of violence against women. They do not personally oppress women, but they do not

distance themselves from men who oppress women. They do not make sexist jokes, but when another man makes such a joke,

they laugh. In short, these men, who are the majority of men in the world, do not act in a patriarchal manner, but they

do not stand up to patriarchy either. This is because they all benefit from women’s subjugation.

Poetry Manifesto: “We will not be Bystanders”

The Poetry Review, 108:1, Spring 2018

Good poetry of witness can enrich our understanding of humanity, tell the truth in its full complexity, highlight the

failure of conventional morality at desperate times, show how violence disconnects people and destroys normality and

domesticity, and generally address the grey areas that we avoid in our everyday lives.

I now know that good poetry of witness comes from that soreness, from feeling outrage and fear, from that place where we

are bewildered, and we feel too much. Poetry is not science. We cannot speak the truth about suffering in poetry when we

haven’t emotionally experienced it. Understanding alone does not help convey the emotional tone of desperation, and it

does not help rebuild the connections that have been severed by victimisation. So yes, we need to be willing to suffer,

to share pain, to feel strongly. But this does not mean that our poetry should be ‘emotional’.

Sherko Bekas’ Butterfly Valley: Translator’s Preface

Butterfly Valley, ARC Publications, 2018

In a land where beauty and tragedy intertwine, victimhood and agency exist side by side, devastating events take place

without causing a stir in the world, and the difference in temperature between the harsh winters and blazing summers can

be as much as 50 degrees, poetry has to live up to and reflect these extreme conditions of life.

Both Anfal and Halabja are central to Butterfly Valley. Early on in the poem, Bekas evokes Halabja by speaking of the

“doomed spring” and “the frost of March.” He expresses yearning to go home and embrace the victims: “the lemon-tree of

their figures / poisoned in March.” The extremity of the tragedy makes it impossible for Bekas to have a unified and

simple reaction. It is impossible to grieve in the usual way.

The pain of these events distorts Bekas’ sentences and scenes. Normality is a luxury that has been destroyed. In this

genocidal atmosphere “knives rain in the wind,” “blood flows / from the stone’s cave- wound,” and “the sound of gushing

blood / reaches the ears of history.” The large-scale destruction creates confusion and chaos such that abstract and

material things – humans, animals, and inanimate objects – are confused with each other:

– Is this poetry’s left behind locks

or the forelock of a village’s dream?

Is this a sun-ray’s broken mirror or a girl’s? And this murdered river

was she a field’s beloved or a boy’s?

And this fallen scream

was it my mother’s scream or a tree’s?

Is this a nipple or a cherry stone?

Is this a burnt cat or my baby?

Is this my father’s head or the bread-pad? Are these an angel’s fallen wings or a dove’s? Are these my irises or olives

and grapes?

The poet doesn’t know “how to separate them from each other.” The world has become surreal, deformed and messed up by

destruction, and Bekas mourns with every inch of his body and soul. He feels that he has no choice, the only thing he

can do is to write: “You had to do this / to write poetry with the tip of flame / and set fire to your fear and

silence.”

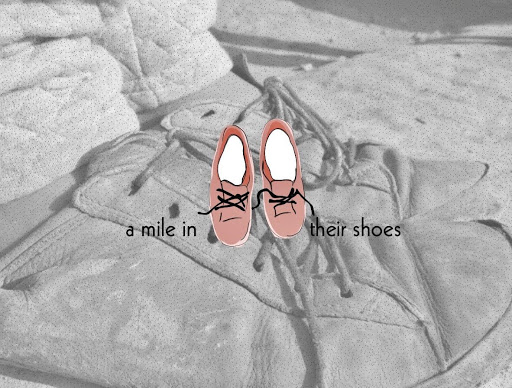

Towards Becoming a Survivor, Êzidî Women Shedding their Shoes

Beyond Borders Touring Exhibition: A Mile in their Shoes, 2015

The Yiddish poet, Moshe Szulsztein refers to the remaining shoes of Holocaust victims as “the last witnesses.” Our shoes

are a witness to the journeys we take, they carry us into different phases of our lives, into adulthood and maturity,

love and heartbreak, war and imprisonment, rape and slavery, escape and freedom. In August 2014 the shoes exhibited here

stopped being a witness to innocent walks to school, to the bazaar, and to friends’ homes. These shoes witnessed kidnap,

murder, sexual abuse, enslavement, forced conversion to Islam, and later escape and reunion with friends and family.

The connection between shoes and violence is not new. The worn-out shoes, found in concentration camps at the end of

World War II, were divided up between various Holocaust Museums to honour the victims. In Budapest, sixty pairs of shoes

were cast of iron and attached to the Danube bank to commemorate the Jews who were ordered to take off their shoes there

and then shot and taken away by the river. What is new about this exhibition is trying to trace our recent history,

which is about derailment, through Êzidî women survivors’ shoes.

This exhibition offsets war and brutality. It is about the fate of those whose painful journeys we track through their

footprints. It is an attempt to acknowledge their ordeal, return their lost identities to them and restore their

humanity, so easily ignored by the oppressor. The stories of these shoes defy those who disrespect human beings just

because they have a different ethnicity and religion, or because they don’t share a history with them. They defy those

who try to wipe out identities other than their own, to kill, enslave, and silence them.

Social scientists have long argued that history is written by the dominant groups, their version and voice excluding

other versions and voices. Women are one of the groups whose experiences of national catastrophes are considered

irrelevant to history. There is evidence that these side-lined experiences are then gradually lost or “forgotten” (1).

It is therefore essential to listen to the ‘hidden voices’ of women and other oppressed groups to ensure that their

experiences inform our history. At times, however, including women’s marginalised experiences is not so straightforward.

This is particularly true when sensitive issues are concerned.

Rape in settings of armed conflict is used for physical torture, disempowerment, and humiliation of the victim and her

group. In many societies, rape causes social stigma. Women survivors of rape are usually left with difficult memories

that have “no easy access to public space even as they [are] ... constantly invoked or alluded to” (2). Similarly,

although the sexual enslavement of Êzidî women has become part of the public discourse, individual survivors find it

difficult to speak out. This is because speaking may cause further stigma and shame as well as psychological

retraumatisation.

Soon after the first women managed to escape Daesh enslavement in August 2014, the Êzidî spiritual leader, Baba Sheikh,

urged members of the community to welcome the survivors back and care for them. This, however, does not mean that

everything is okay now. The stigma remains and it will be difficult for young, unmarried women to find husbands after

their ordeal has become public. There is also stigma around those who became pregnant as a result of the rape. There are

recent reports about doctors in Kurdistan performing illegal abortions (abortion is still illegal there) on women

survivors and secret surgeries to ‘reverse loss of virginity’ of the victims. The social shamefulness of these issues

may be one reason why women may remain silent. It is also possible that some women find it too painful to talk about

what they have endured. Even though some people find talking about their experiences therapeutic, others may not feel

the same. Talking about the past can bring it alive once more, and this may be something that many women are trying to

avoid.

Êzidî women survivors are called on by activists, researchers, journalists, and governmental workers and urged to speak.

They carry the burden of telling the truth. The survivors here find themselves in a paradoxical situation. Disclosing

such issues is particularly difficult in a patriarchal society that, on the one hand, pressurises women to speak about

their experiences and raise awareness about their victimisation by the Daesh forces and, on the other hand, victimises

women who are known to have been raped. This is why this exhibition is important. While bearing witness to this painful

history, these photographs protect the identity of the survivors. It works on the principle that we do not need to see

the faces of those who suffered in order to understand and relate to their suffering; looking at their shoes is good

enough. These shoes are being shed because the women shed their identity as victims and step towards being survivors

with all the resilience and strength which this shift brings.

Memories of oppressed groups must inform our history in a way that would restore respect and dignity to them and not

further victimise them or reduce them to eternal victims. By listening to and reading these stories we condemn a history

where religious totalitarianism and nationalism attempt to destroy pluralism in our societies and disregard human

uniqueness. We need to restore respect in our communities, to create a community where every individual, regardless of

their ethnicity, religion, gender, and sexuality, is respected and their dignity is preserved. Like Germany, we should

learn from our history and reiterate: “Human dignity shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of

all state authority” and indeed each and every one of us.

Ringelheim, J. 1998. ‘Genocide and gender: A split memory’, in Ofer, D. and Weitzman, L.J. (eds) Women in the Holocaust.

New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Grossmann, A. 1999. ‘A question of silence: The rape of German women by occupation soldiers’. October Magazine, Vol. 72.

Ktd ad(?) Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

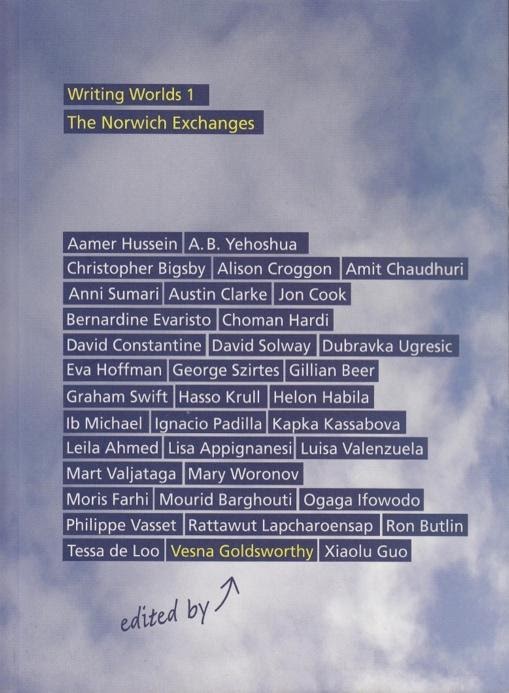

The Pleasure and Duty of Writing

Writing Worlds 1, The Norwich Exchanges, 2006

Discussing the value of a work of art can lead to many debates. Despite the difficulties with Kant’s discussion of

artistic value I agree with him that this is partly determined by the pleasure we drive from it. This pleasure cannot be

moral, he argues, neither can it be sensual. Kant distinguishes between three kinds of pleasures: the pleasure we get

through doing the right thing, i.e. “moral pleasure,” the pleasure of eating and having sex, i.e. “sensual pleasure,”

and what he calls “aesthetic pleasure.” Aesthetic pleasure, Kant argues, unlike the other two kinds, is totally

disinterested. By this he means, we do not enjoy a work of art because it satisfies an end for us (be it moral or

sensual) but we enjoy it as an end in itself. For a piece of writing to be valuable, it needs to please us not because

it is a moral piece of work, neither because it sexually excites us (for example), but because we can take disinterested

pleasure in it.

The question which arises here is what exactly is this ‘disinterested pleasure’? Kant argues that a poem, for example,

is valuable because it has an aesthetic idea which is expressed in a way that quickens our senses. By reading a good

work of art our mental faculties (by which he means the imagination and the understanding) are in harmony and perfection

with each other. Hence a valuable work of art has the capacity to make us feel more complete. This does not mean that a

work of art cannot disturb or puzzle us, but that in doing so it brings our mental faculties into a sort of togetherness

which may explain why we derive pleasure from tragedy. There are many objections to Kant’s aesthetic theory but I will

not go on to discuss these issues. I have merely introduced Kant’s theory because it is a good introduction to what I

want to talk about next. I will try to bring in some of the points that were raised by the writers during the symposium.

Two days ago, Mourid Barghouti talked about how, more than ever, the notion of shared space is threatened, about the

ambiguities of the meaning of place. He argued that for 69 Palestinian women giving birth at checkpoints and the

children who are born to grow up in a restricted space, their path to school forever divided by checkpoints, the notion

of place, bed, and road are far from ordinary. In reaction to his remarks, A B Yehoshua argued that Mourid’s story does

not deal with the complexity of the situation, and therefore is not fair - it talks about women giving birth at

checkpoints but does not mention why the checkpoints exist.

Yesterday, David Constantine spoke of the importance of translation and of the clarity of language. He argued that a man

who does not think clearly is oppressed. He provided some examples of slippery language, language which intentionally

uses certain words so that the meaning of the situation becomes ambiguous. He provided examples from the Abu Ghraib

prison, how ‘torture’ was renamed ‘intense interrogation’, and the relationship between the torturer and the victim was

called ‘prisoner-guard’ relationship, alongside others (e.g. Michael Howard’s discourse on refugee and asylum seekers).

David Solway argued that David Constantine should have provided examples from both sides of the conflict, for example

the language used by Islamic terrorists is as slippery and ambiguous as that used by the Americans.

In his talk yesterday, Austin Clarke noted that The Merchant of Venice was banned in his university in Canada because of

its racial dimensions. Just before Austin’s talk, AB Yehoshua pointed to the importance of morality in judging a work of

art; how we cannot ignore the moral aspect in works of literature. In the discussion that followed A B Yehoshua’s talk

and Gillian Beer’s response, it became apparent that for many writers the issue of the morality of a work of art does

enter into consideration.

Personally, I have divided feelings about this. On the one hand I think that whether or not a work of literature is

moral, it can be good or bad. If we decided to cleanse the literary scene of all literature that has some racist,

sexist, colonialist, and Orientalist aspects, we may need to demolish many great works of literature. On the other hand,

I am well aware of the power of literature to reemphasize negative stereotypes and to justify the imbalanced power

relationships in the world. Maybe the best thing is to be aware of the moral dimension of the work, without having to

abandon the work altogether. Gillian Beer pointed to the reader’s resistance to morally corrupt issues, which I think is

a key concept in this debate. But this in itself requires a mature, aware, and intelligent reader. For example, I read

‘Gone with the Wind’ when I was fourteen, living in Iran, and I only saw a love story in it. It was only when I was 19,

living in the UK, that I become aware of its racial dimensions.

Eva Hoffman pointed out that we should maybe use the word ‘seriousness’ instead of morality. By this she meant how a

work of literature should expand our perceptions of humanness - its value will lie in how seriously it attempts to do

this. This resonates with George Szirtes’s comment that good literature aims at the truth, and we find profound pleasure

in becoming aware that these human truths exist.

Similarly, David Constantine pointed out that he writes to fight back the current powers that mystify language, and

therefore manage to fill our world with untruths. In this sense, thinking clearly and writing clearly are essential to

reclaiming language and abiding by the truth.

The ambiguity still remains as to whose truth, but I hope that the reader’s intelligence and resistance, Gillian’s

concept, will help him/her to judge the work. Even though truth is not always a black and white matter and there are

times when listening to two sides of an argument, we can understand and sympathise with both. This may be a truth in

itself, to be forever open, to be curious and prepared for a work of art to ‘unsettle us’ (Constantine’s concept).

From my own perspective, I believe that as readers and writers we are forever concerned with truth and justice. I write

to defy the blind spots of truth and justice that exist within all of us. I write to challenge current norms, challenge

the people who decide whose cause is justified and whose is not, whose voice will be heard and who will be silent, whose

suffering is more important than the other. I write to tell my truth, the one that has been side-lined and silenced.

Only when we know the truth can we try to do the right thing.

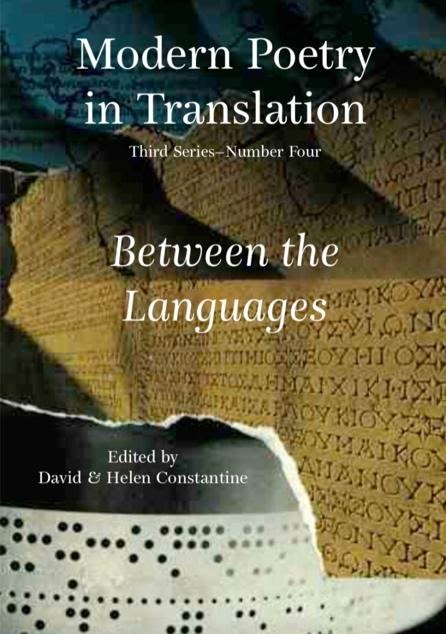

Switching Languages: a Hindrance or an Opportunity?

Modern Poetry in Translation, Series Three, Number 4, 2005

‘What language do you dream in?’ people keep asking me. This is meant to be an important indicator of my natural

language, the language of my thoughts and feelings. The simple answer is, I never remember the language of my dreams.

Does this mean that I dream in Kurdish? Maybe, but should this imply I cannot write in English or that I am constantly

translating my thoughts when I speak and laugh and make love in English? It is possible but unlikely. I go through ups

and downs with my languages. On certain days I feel fluent in four languages, I can hear them all clearly and sing them.

Other days I keep slipping over words even in my native tongue, and finding the right word is a big struggle.

When I came to England twelve years ago all I wanted was to be able to speak and understand English. I wanted to be able

to study philosophy and read poetry without having to use the big Oxford dictionary. I never thought I would write

poetry in English one day. In fact, I was a very young writer when I came and my poetry was developing while I was

living in London. A few years on, when the majority of my friends were English- speaking, I thought about translating

some of my poetry simply to share it with them. I was at university then and my friends looked at my poetry book and

said: ‘It looks beautiful!’ I then translated a few poems which came out really badly. Despite the fact that my poems

were simpler and more down-to-earth than most Kurdish poetry, it was nearly impossible to get it right. At least, this

is what I thought at the time. ‘Yekek bereda teparee, chawekani pir boon le noor’, so one of my poems goes: ‘Somebody

passed from here, his eyes were full of light.’ The word ‘noor’, which is an Arabic word, literally means ‘light’ and

has led to the creation of another word in Kurdish, ‘noorani’, which means someone with the aura of holiness. So the

literal translation ‘someone whose eyes were full of light’ does not have the implication that he is holy in a

super-human kind of way, and this is an important part of the poem. My translations of my own work seemed bland, so I

decided not to try.

Over the years, through my education, friendships and readings, my English became stronger, more natural and

spontaneous. Through reading contemporary English literature, my style of writing gradually changed, my language became

simplified and my images more pinned down (I am still not sure if this is a good thing). On the other hand, the longer I

lived in England the more I realised there was little understanding of the Kurdish situation in the Middle East and

therefore no real sympathy. This realisation made me angry for a while but soon I became conscious of my position as a

Kurdish writer in the UK and the responsibilities that came with that. I realised that instead of being angry, I could

write in English about the truths that are so important to me and are unknown to others. In this sense switching to

English happened on two levels, linguistically and politically. On one level I can say that writing in English was by

choice, on the other, it was just a necessity. When I started toying with the idea of writing in English, there was a

period when I wrote in both Kurdish and English. Most of the time the poem itself decided what language it wanted to be

written in. ‘Jamek aw ba dwaya birjin, beshkum zoo bigeretewe,’ I wrote: ‘Spill some water behind him, hope that he

comes back soon.’ This may seem meaningless in English but in the Middle East when someone goes away you spill water

behind them so that they go and come back safe, like water. Such thoughts, words and idioms determined what language the

poem would choose. Unfortunately, I now only write in English. Languages which are used more intensely have the tendency

to take over like that. At times I feel sad when I think I may never write in Kurdish again. Other times I think that as

much as English can claim me, I can claim it to tell my truth and give my community a voice. In the end, language is

music and as long as this music becomes part of us, we can be creative through it. Also, we can recreate our identities

in any language and writing in English may not be as big a betrayal as it sometimes seems.