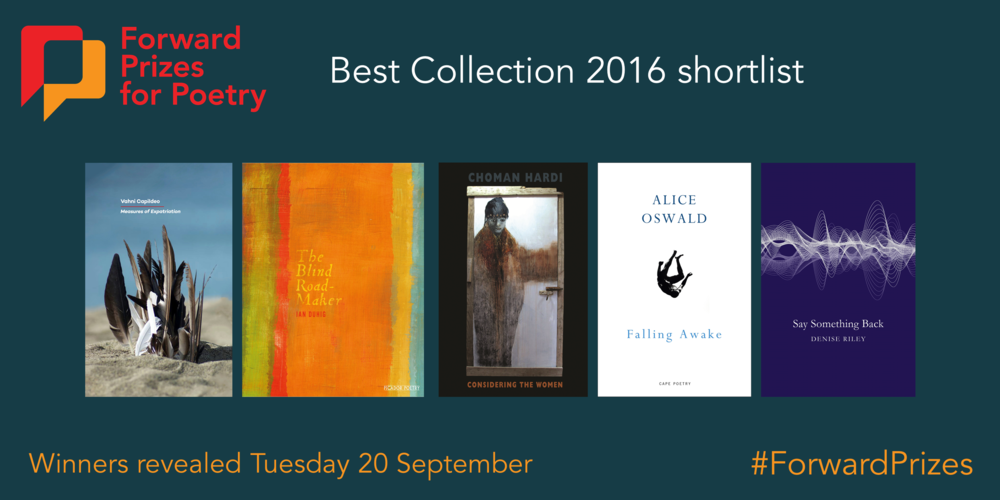

Shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best Collection

Shortlisted for the Forward Prize for Best Collection

Choman Hardi’s Considering the Women explores the equivocal relationship between immigrants and their homeland - the constant push and pull - as well as the breakdown of an intermarriage, and the plight of women in an aggressive patriarchal society and as survivors of political violence. The book’s central sequence, Anfal, draws on Choman Hardi’s post-doctoral research on women survivors of genocide in Kurdistan. The stories of eleven survivors (nine women, an elderly man and a boy child) are framed by the radically shifting voice of the researcher: naïve and matter-of-fact at the start; grieved, abstracted and confused by the end. Knowledge has a noxious effect in this book, destroying the poet’s earlier optimistic sense of self and replacing it with a darker identity where she is ready for ‘all the good people in the world to disappoint her’. Hardi’s second collection in English ends with a new beginning found in new love and in taking time off from the journey of traumatic discovery to enjoy the small, ordinary things of life. Poetry Book Society Recommendation.

Production Date: 22 Oct. 2015

Publisher: Bloodaxe Books Ltd.

Paperback: £9.95

ISBN: 978780372785

E-book: £8.95

ISBN: 9781780372792

Pages: 72

Size: 216 x 138 mm

Rights: World

The centre-piece of Considering the Women is ‘Anfal’;

a devastating sequence comprising testimonies from

survivors of one of Saddam Hussein’s most brutal and

far-reaching evils…

Hardi takes on this dark period in

her homeland where there are no true victors, and she

sees to it that history can be written by the survivors.

Considering the Women is impressive in the sense that it leaves

its dent upon the reader.

I came away from my first reading dizzied,

imbalanced and ashamed in a way which I have not felt

since first encountering the work of Primo Levi.

The collection delivers snatched fragments

of the Kurdish story to an Anglophone audience and enacts

the uncomfortable yoking of an adopted nationality with fading

memories of a crumbling homeland.

Choman Hardi’s unsparing exploration of the plight and

flight of the Iraqi-Kurdish people in the 1980s is poetry

of witness of a high order. This is a body of work which

is unique and deserves as much notice as we can give it.

Hardi’s language is always sufficient to the task – plain,

direct, rising to the occasional metaphor, natural enough to

suggest a witnessing voice.

It’s brave and right of her to reflect her own life’s travails

in these poems as it is always the individual’s experience

that is trampled by state power and any re-statement of its

importance is a political act.

The central sequence is stunning. It begins with a statement by

a researcher who intends to document the experiences of

the survivors of terribly suffering and “make sure your voice is heard”.

This is followed by eleven testaments of such horrors as

women’s prisons, death pits, concentration camps, and gas attacks.

Finally, there is a coda from the researcher,

her initial enthusiasm for her project and optimism for the

difference documentation will make shattered:

“Sometime ago when I started, it was all clear, I knew /

what had to be done. All I can do now is keep walking, /

carrying this sorrow in my soul”.

There are any number of places in the school curriculum where

this poetry would prove illuminating, and it really should be read.

Choman Hardi’s poem ‘Gas Attack’ comes from the ‘Anfal’ sequence in her recent book,

Considering the Women (Bloodaxe, 2015). The narrator is a woman whose community is

bombed by the Iraqi state in the notorious attacks on the Kurdish people in 1988. Wilfred

Owen’s famous poem (‘Dulce et Decorum Est’) draws on his experiences of trench warfare

on the Western Front in World War One. Owen’s title is a reference to Horace’s Odes (III, ii

l. 13), the full phrase translating as “Sweet and fitting it is to die for one’s country”. It is this

sort of ardent, patriotic jingoism that Owen looks to counter in the poem as it is the world’s

blindness to real events in Kurdish-Iraq that Hardi wishes to correct.

Owen’s poem takes the reader into the trenches, to the post-traumatic world of nightmares,

but also manages to encompass this declarative, even propagandist, point. Likewise, Hardi’s

poem plunges us into the gas attack and its aftermath but never ventures into the same

argumentative, passionate point-making. Her decision to allow the details of this poem to

speak for itself is a brave one (of tone and manner) given the horrors of which it speaks and

the author’s evident commitment to bringing them to notice.